from *The Birds Know, So*

with Rob Halpern

We are living whenever

In a scholastic bunker

The question what we are

Doing fills our lungs

The ‘invented’ world

And the remains

Of the earth no longer

Being of the world

I try to fill myself

Up with may and not

Can I try to fill these

‘Terrestrial voids’ with me

So locate where we are

What commons flinging us

Sings late enclosures

No theory will invert.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Monday, August 11, 2008

First Last

All the horizon lines

and hatchets sing us free

prosody these pieces

of the real

what we allow into

that field and what permits us

malice the salvages of

steeples burned

out long ago

places unpeopled become

peopled the "last

first people"

the first last

but will any one be left to

convert your testament to action?

crude dries up we are

too many million to system

we turn to shale

we turn to corn

strategic resources issue alibis

the violence in pro-

cessions

in longer

marches a violence

of number

what will

happen they begin in songless

ness a path

of giants paved by

Malthus

strange math

which makes the world up.

and hatchets sing us free

prosody these pieces

of the real

what we allow into

that field and what permits us

malice the salvages of

steeples burned

out long ago

places unpeopled become

peopled the "last

first people"

the first last

but will any one be left to

convert your testament to action?

crude dries up we are

too many million to system

we turn to shale

we turn to corn

strategic resources issue alibis

the violence in pro-

cessions

in longer

marches a violence

of number

what will

happen they begin in songless

ness a path

of giants paved by

Malthus

strange math

which makes the world up.

Saturday, August 09, 2008

Allegories of Disablement (Talk)

Here is a talk I presented a few weeks ago in San Francisco for the Nonsite Collective's emerging curriculum around disability and poetics.

Click here for the version at the Nonsite Collective's website accompanied by Patrick Durgin's astute commentary, or read below.

***

Allegories of Disablement: some consequences of form towards potential bodies

Wandering the artist’s monographs at a University of Maryland library in the spring of 2006, I came across the following:

Possibly, in earlier pieces, I used the body as a proof that "I" was there—the way a person might talk to himself in the dark. So, with that assumption—that the body was analogous to a word-system as a placement device—there was an attempt made to "parse" the body: it could be the subject of an action, or it could be the receiver, the object (it should be noted that most of the earlier pieces were kinds of reflexive sentences: "I" acted on "me."

This initial fragment, from a monograph of Vito Acconci’s work, among other materials I’ve gathered in the past few years, has led me to a prospectus of sorts, if not an inchoate essay on what may be called “disability” in relation to practices in poetics, architecture, design, “live art,” and movement research.

What interests me about the Acconci quotation, is how it may encapsulate a larger discourse occurring in the late 60s and early 70s. This discourse, I believe, concerns the constitution of subjects as they are extended in space by movement, language and image; it also concerns what I will call, after a remark by Martha Rosler conveyed to me by a student of hers in conversation, the performance of the body mediated by the imminent threat of harm.

For artists like Rosler, Acconci and others to grow-up and make work in the media environments they did, in which graphic images of the body under threat—those abroad in Vietnam, and those suffering civil strife and disobedience “at home”—were being widely disseminated by an accelerated and avid mass media, meant making work in response to specific images of violence, but also to qualitative and quantitative transformations in how information of and about graphic violence was being conveyed. While such responses were, as in the case of Rosler’s “Bring the War Home” photo-collage series, a matter of strategic reappropriation of text and images from media sources, they also made the body a site for the production of new images, if only fleeting ones, and the undertaking of actions both critically reflective, symptomatic, and therapeutic after Vietnam.

While poet John Taggart often gets flack for his poem explicitly after Vietnam, "Peace on Earth," since Taggart, in the words of Eliot Weinberger, was not a participant in the “arcadia” of 60s activism and counterculture, one way to read beyond this criticism is in terms of Taggart’s own insistence that his poem is one of healing, not reportage or eyewitness testimony. In the interest of healing, Taggart arrives at a form after 13th century Gregorian chant (round or cantor) and the 60s incremental music of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. In this way Taggart’s project can be seen alongside those of a host of musicians, film and visual artists who in the 60s sought through forms means of healing, well being, and reformation, looking forward to the traumatic effects of the war upon a civilian culture. Pauline Oliveros, Tony Conrad, Terry Riley, Paul Sharits, and the Living Theater of *Dionysus 68* all come to mind here.

Yet, hasn’t art often asked its viewer to empathize with images of violence, to undergo this violence and respond in various ways? I think of Goya’s “Disasters of War” drawing series, which Susan Sontag considers at length in her book, *Regarding the Pain of Others*, or well before Goya Medieval depictions of the crucifixion. Although the later sought to promote fear and passivity in its viewer, both functioned to activate affective response in the interest of certain effects. Closer to the 60s chronologically if not synchronically, are the Dadists as they sought to present the body under threat through performances which channeled the violence of war, as well as the particular social antagonisms which made the first World War possible. This, in fact, seems the real content of Dada’s “experimentalism”: an anti-representational, however often mimetic, performance of the body under threat.

While I don’t want to reduce 60s/70s art to a particular cause, the looming presence and problem of Vietnam in the popular consciousness of the period no doubt plays a huge part in shaping the most important art of this era. In Acconci’s statement above, summarizing his late 60s/early 70s performances before he would turn to installation and audio-works, and eventually public sculpture, design, and architecture—a career arc which pretty much mirrors that of his contemporary, Arakawa, who with his partner, Madeline Gins, founded the Reversible Destiny architecture project—Acconci recognizes a fundamental split in the subject which all of his work of the period enacts.

Is this caesura of subject and object—for itself and in itself, “I” and “me”—embodied by a particular grammar—“the body… could be the subject of an action, or it could be the receiver, the object”—the result of a transformation in the way the subject is conceived in relation to mediated violence? Does it point to an empathic impulse augmented and transformed by late discourse networks—the fact that the body is conceived and formed by information, that it is a perceptive body as well as a “real” body with real physical limitations; or that the “real” body was always a cybernetic one. These conjectures, albeit ungrounded by any real neurobiological evidence of how images affect the brain and the larger organism via its relationship with the brain, are in the larger interest of understanding art after Vietnam as we live with its legacy currently in relation to Iraq and other imperial conflicts. Likewise, these conjectures are in the interest of thinking about movement research and aesthetics towards the potentialization and healing of the body, as the body intends consciousness, feeling, and common sense.

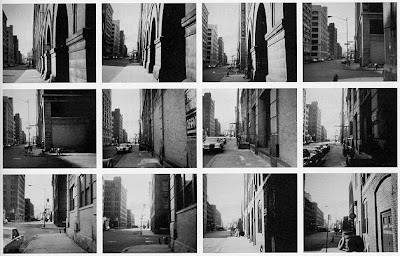

In Acconci’s photo works of the period, it is as if photography in tandem with language acts as a kind of prothesis or extra organ for cellular memory as cellular memory virtualizes movement in space. The artist photographs himself spinning around until he falls to the grass; he walks the streets under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass in Brooklyn taking photos at each street corner; he takes a picture every time he blinks. During the same period, Acconci enacted a series of works whereby his own body became a kind of measuring device or index for the space around him—on city streets, at the beach, in the woods, between art galleries and his home. Is the artist’s body measuring the world—to encompass or territorialize it? Or is the world measuring him—as if to prove the existence of his own body, to ground this body in actual spatial relations and dimensions: “the way a person might talk to himself in the dark”?

What these works record obsessively is negative experience: losses of perception as they echolocate a subject formed by sensory-motor dislocation (now you see it, because you once didn’t). After the fact of Vietnam—the actual bodies abused and mutilated by war on any side; the harrowing journalism as it made legible and accessible images of cultural violence the products of American sovereignty—to “parse” (Acconci’s curious term for his activities of this period) seems to evidence a caesura of the person as a persistence of information about the body in space-time. Physical space and a space of images coconstitutive with one another; physical space, and the image-body, and a blank through which the body in space comes into being.

Other examples overlap from the period. LANGUAGE magazine coeditor, Charles Bernstein’s first chapbook publication is called, *Parsing*, and features a series of language games after the term from computer science and linguistics. There is Madeline Gins’s book, Helen Keller or Arakawa, in which Gins correlates the perceptive dilemmas of the blind and deaf Keller with those of her partner, Arakawa, fusing incidents and musings of the writer/philosopher/probable founder of disability studies and activism with descriptions and reflections on works by the Wittgensteinian painter/sculptor/installation artist/architect. Though the book was written in retrospection of Arawaka’s late 60s and early 70s work, it is interesting Gins’ uses of the term "cleave"—a near synonym of “parse”—to describe the primary act of perception involved in encountering this work as it resembles Keller’s own poetic descriptions of her extraordinary sensory-motor circumstance.

For Keller to act in the world and therefore be “world-forming” or “cleaving,” not unlike Arakawa’s participant-viewer before one of his synaesthetically challenging canvases, installations or architectural objects, is to become necessarily “aesthetic” or “poetic” (where poesis derives from the Greek for the term “craft” and refers to an “active making”). The works of Arakawa/Gins, force their viewer-participant to react by creating conditions which may be said to augment disabilities and impairments latent or virtual in the “abled” so-called. These works intend new capabilities—actions, perceptions, sense awarenesses, ideas, movements—by both disengaging habitual sensory-motor functioning, dramatizing situations of chiasmus (the simultaneous recognition of cognition (what is thought reflectively) and sensibility (what is felt or sensed as an immediate data of the body)), synaesthesia (“seeing out of one’s ears” as Arthur Russell has it), and negative synaesthesia (the “eyes not having heard” of Shakespeare’s Bottom).

[examples from Arakawa’s painting here]

The following is from Robert Kocik’s *Overcoming Fitness*:

Are there glorious states without fitness? Undeserving and elated? Gratuitous and undying? Aren’t vulnerability and hunger advantageous too (Athens became a philosophical power only after losing its navy)?

That’s precisely what blessedness does—it overcomes fitness. The beatitudes, pronounced by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount, brought invaluable symbolic liberation. The democratization of happiness. Woe to the rich for they have already got all they’re ever going to git.

But the beatitudes themselves have only begun to materialize rather recently—applying themselves not to an otherworld or kingdom come but to current socio-economic conditions. Since 1525 when Thomas Muntzer caught cannonballs with his bare hands while leading the Peasant Revolt we’ve been in a period of material beatification. The Last Judgment is for the living.

And this from Kocik’s Rhrurbarb, a prosodic “emergency response” to his mother death:

Because in turmoil, healthy.

Because overextended, healthy.

Because overwrought, unbegun.

* Disservice*: secret name of God.

The following is from an introduction I wrote for Kocik in May of 2007, and presented at Peace On A events series in Manhattan:

While Kocik’s work encourages obsolescence, mis- and dis- use, it also remains entirely useful and generative thru what it can do. Perhaps it is generative in ways similar to disability. For to disable is finally to show how something works by how it doesn’t—it is “knockout” as Kocik puts it; more so, however inadvertently or fortuitously, disability posits the subject at the indiscernible points, the blindspots, where a technology—that which works, or functions all-too-well—has failed to maintain its instrumentality in relation to a user for whom the existence of that technology would otherwise recede in use. A tragic failure to privilege disability I find echoed in Augustine’s lament, which Kocik quotes throughout Overcoming Fitness: "if only they had found a use for the world without using it." To become prosodic body, then, is to occupy those obscure locations, place holders, purchases and pivots where I is not any longer I because it won’t work—so is unmade, inoperative, disabled, and only thus substantiated.

To contrast Robert Kocik’s work here with that of Gins/Arakawa, I believe theirs to be a kind of foil for Robert’s own. Where Gins/Arakawa strategically disequilibrate the sensory-motor coordination and perceptive habits of the “capable” so-called in order to promote eternal ability as “not dying” (Gins/Arakawa’s term), Kocik is more interested in activating ability in the “disabled” so-called, as well as the inverse. He achieves this by means of an elaborate toolbox he has amassed via research in poetics, theology, philosophy, anthroposophy, official medicine, alternative medicine, architecture, dance, biology and design. His recent umbrella term for these tools is prosody. Through prosody Kocik provokes ability—movement, health, thinking, conatus, communication—from a position that presupposes disability as a universal condition of being human or, for that matter, living; that through this condition we can discover advantage and affirm difference. In this way Kocik is a late practical philosopher of overcoming, grace and lightness; like (a certain) Darwin before him, Henri Bergson, Nietzsche and Deleuze, Kocik would have us—apparently human, apparently mortal—capitalize on our “fallen” condition, indeed celebrate it. Recognizing potentia in disability, disability is critical for the achievement of this overcoming. In contrast to Robert’s design practice, thru which he builds structures to practically empower the “disabled” and “abled” alike, Gins/Arakawa’s architectural works appear funhouses of sorts—the manifest fantasies of a wildly generative, however largely metaphoric, conceptual-aesthetic apparatus (all the words, drawings, painting and sculptures which precede the construction of actual architectural structures at the enormous expense of the artists’ benefactors and commissioners).

The following is from Eleni Stecopoulos’ 6/3/08 post, “Response to Disability and Poetics” at the Nonsite Collective website:

“Aesthetics: the improvisation I make of my sensitivity syndrome.” (from _Idiopathic_.) Aesthetics can’t come but from the intelligence of our conditions. All our asymmetrical intelligent bodies. Disability founds aesthetics—-for all persons, not just those with disabilities. If we became conscious of that, perhaps we might start to see how all our conditions determine our forms, how architecture—-physical, social, legislative—-determines all our access. Robert Kocik enters in here: how can architecture, then, treat conditions of inaccess and facilitate aesthetics?

So disability, as Eleni Stecoupolos has put it, is a kind of first aesthetics, where the aesthetic—what is made, what is built or constructed—is the result of conditions of possibility which may derive from limitations, decisions, conditions and determinations indicated by the prefix *dis*. Following Kocik’s intuitions communicated in a private e-mail the other day, that language should now be sufficient to achieve what his architecture and design practices otherwise achieve, disability may also be first poesis—active making in opposition to docility as it manifests in fitness regimes, mechanism, ratiocination, and telic “ablity”—ability where ends justify means.

A problem of discussing or “theorizing” disability, foreseeably, as a lived circumstance linked to the practical realities of specific social struggles—struggles to change the way actual bodies navigate everyday life, for example, or are privileged as subjects and citizens—is that the term would be taken as an indication of lack or insufficiency—that is, as a negation rather than an affirmation of difference. What I realize, when I consider the term disability—both as a political identity and as an ontological formation—is to what extent this term should denote abundance rather than lack. What I believe is consequential in terms of a discourse about disability is the future of consequence itself—ways of proceeding in the world which affirm and activate conditions of possibility, and which make good on opportunities, promises, debts of overcoming.

It is interesting that two “tests” of avant garde poetics in the 70s are, coterminously, Hannah Weiner and Larry Eigner. Whereas Weiner’s abuse of LSD in the late 60s led her to hallucinate text on her own body and in her immediate environment, Eigner’s struggles to write with Cerebral Palsy left their mark in concatenated syntactical patterns, radical uses of line spacing, and of the typewriter as a site of composition. While one may initially be struck by the quotidian content of Eigner’s work, where what appears repeatedly are the words “trees,” “birds,” “windows,” and other common nouns, the real content of the work may be Eigner’s own struggles, physically and psychically, to write. In Eigner’s writing it has rarely been so clear that embodiment—having a body that affects consciousness—cannot be separated from composition, whether as a performance or intention. Likewise, in Weiner’s case, while Weiner’s “clairstyle” (that form of writing by which she gave form to her inner experience of textual hallucination) is obviously shaped by counter-cultural art and literary forms such as Happenings, Intermedia, and New York School poetry, it also clearly originates from bio-chemical transformations in Weiner’s person brought on by LSD use in tandem with her own idiosyncratic thought-experiments, literary performances, and lifestyle choices. As Patrick Durgin has pointed out in conversation with me, these decisions—the choice to become “clairvoyant” and a “silent teacher” (Weiner’s terms for her visionary practice)—introduced difficulties that Weiner lived with until her death in 1997, difficulties which resulted in extreme self-care regimes, as well as the intermittent search for care among her community and friends, if not official medical channels.

A discussion of Weiner, Eigner and other artists of “disability” so-called always risks fetishizing the conditions of their compositions in the interest of making a case or proposing a thesis, and thereby greasing the wheels of literary theory and scholarship. In discussing their work here, I realize I am complicit in this academic tendency. Yet I return to Eigner and Weiner’s writings more or less constantly because they teach me about myself, and principally about writing as it intends the world I live in, and occurs in relation to it. They teach me that what one does on the page or before their materials is never separate from a bodily or psychic circumstance; that, as Robert Creeley refrains in one of his poems, “the plan is the body”. What Eigner and Weiner prove, is the extent to which any one body is always already disabled when they compose; they augment this primal condition, and so I value them—their bodies, their minds affected by their bodies—as they reveal particularities of my own, and possible universals. So, perhaps, any writer or artist who has achieved anything with form, may be said to have worked within disability, or discovered disability as that condition of embodied consciousness which is not a priori, and so intends thinking, vision, understanding, and inquiry without telos.

After an unpublished work by Brenda Iijima, *Remembering Animals*, I have tried to think about Iijima’s use of certain punctuating and diacritical marks in terms of an allegorical dimension of the work. This allegorical dimension has everything to do with how formal choices perform meanings and reflect a reading practice that may be said to be embodied, or intend modes of embodiment through a reading practice. The following is excerpted from a piece on Iijima’s poetics forthcoming in the inaugural issue of the magazine ON, which I coedit. With these excerpts I conclude in the interest of conversation and discussion:

Beyond any procedure or form clearly operative in the work, Iijima’s work moves, and in its movement constitutes an intention beyond descriptive, narrative or propositional qualities of the poem per se. This movement can be discerned in the lines themselves, and line breaks and tabbing in particular, but also in the ways the work has been scored by punctuation and diacritical marks. Throughout Iijima’s work I am struck by her use of parentheses as they delay a reading consciousness, as well as her similar use of bullets in Animate, Inanimate Aims, where these bullets (in succession of twos) function somewhere between a hyphen, ellipses, and periods (because they resemble them). Iijima’s use of these marks remind me that the poem can be a forming space for perception and consciousness. Through them Iijima attends and dramatizes the fact that she and her reader have bodies, are embodied consciousnesses, and that syntax can determine this.

The problem of these punctuation/diacritical marks lead me back to some of the subtler shorter poems of Louis Zukofsky (“Proposition LXI,” for instance, from the series poem, “29 Songs”), as well as Stein’s sparse use of commas, and avoidance of question marks, semi-colons and colons altogether. However I think even more of the ways Leslie Scalapino uses parenthetical marks effectively to create a dialogical consciousness within the poem (reading consciousness delayed in its reading and reflection upon what is being read in different textual intervals and durations) as well as Hannah Weiner’s “interruptive” and “telepathic” texts. These marks are also cleaving as they intend active perception and reflection simultaneously as a singular event of consciousness. I am also reminded of Larry Eigner’s struggles to articulate his unique embodied consciousness through the use of his typewriter, and how the traces of this struggle, a struggle neither merely neural or physical, hinge on certain concatenations of grammar, as well as spacing and recursive dynamics between words, phrases, and sentences (when sentences should occur at all).

In this way Iijima may be said to disable herself, or better yet realize writing as a condition of dis-ability where the intention of the writer is to enable active perception through the page as well as the instrument of writing (in Iijima’s case the computer keyboard of a word processor as well as, I can only imagine, notebooks) mediating this process. While one could say that these marks merely score, I think they do more than score. What they do is site an embodied consciousness coming into being within the world (the page as an intention of the world)—what Madeline Gins calls in her book *Helen Keller or Arakawa* the “forming blank”. Beyond scoring, the marks are what make this conveyance possible between reader and writer, one embodied consciousness circuiting with another. As the consequences of such markings have been little explored in writing, Iijima is brave in her doing so. In this way, I feel like she is advancing little advanced ground for the ways we experience composition as a force potentializing thought’s body, its ever twisting and folding substance.

…[the following passage, from the same piece, concerns the photo-copy before you…]

Several sections from *Remembering Animals* [an unpublished MS by Iijima] are entitled “Cries,” and these “Cries” (the cries of animals? the cries of the poem presenting the cries of animals remembered? the cries of us—humans who are reading and thus mnemotechnical (i.e., remembering animals?)) engage one of the ultimate problems of Iijima’s poetics as it puts an embodied consciousness in relation to political, ethical, social and soul-searching ends. This problem is one of empathy.

When I attended a series of panels about Leslie Scalapino’s work at St. Mark’s Church in October of 2005, organized by Iijima, I remember Iijima discussing Scalapino’s work in terms of neurological research, and mirror neurons in particular. Mirror neurons constitute an activity within the brain activated when one feels empathy. Or, rather, they are what initiate empathic reactions when we recognize the embodied presence of another person: when we see or feel them through cognitive-imaginative contact. In some way, I think the idea of mirror neurons guides Iijima’s own formal practice as she would like her reader to feel something through her work—for others, for animals as an other related to human others, for an ecology felt through these others, for an ecology that is an other (the Other?), for all others to be felt through particular uses of language.

In terms of poetry, mirror neurons “fire” through description and narrative tension, but more so I believe them to take effect through the feeling for words where they intend meaning rather than merely communicate or describe reality. In evoking the struggles of animals in relation to human challenges, Iijima would like us to feel their cries, if not remember them in relation to human ones. The way these cries are felt are through linguistic elements that are under-utilized (and radicalized) by poetic discourse, and yet the stuff of poetry‘s essence: sound, rhythm, movement, prosody, graphology. Once again, the grammatical/diacritical/punctuating elements of Remembering Animals underscore this fact, as double bullets and parentheses … are replaced by multiple dashes (lines) between words, phrases, and other graphic features which shape new habits of reading and encountering language on the page. Like many of Iijima’s idiosyncratic uses of diacritical and punctuating marks these marks allegorize the struggle to reform embodied consciousness. For multiple dashes to cleave textual units between and within lines is to effectively activate a reader’s sense of their embodied consciousness, and thus their responsibility before the page as a site of composition where the stakes of composition are high—an ethical demand.

In the case of the animal body, such bodies are in need of literal reformation and remembrance as they are eviscerated by scientific experiment for causes both humane and inhumane, and historically reified by Western discourses. In the case of the human animal, formally radical writing since the 60s has proven that in the face of empire and the strengthened sovereignty of exchange value the development of new compositional modes and strategies has become central to ways reader and writer are reformed and rendered through composition. After these cultural exigencies, the more “polished” and mannered writing of my generation seems totally outmoded by Iijima’s own insofar as her work abandons received lyric qualities, syntaxes, grammars, prosodies and generic distinctions, eschewing manner and categorization for effectiveness, activity and creative affirmation (joy, blessedness).

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Some Nonsite Poems

“For every pile there is a pit,

for every pit, there is a pile.

For every heap of architecture,

there is a terrestrial void.”

*

For Lee

A devil’s refusal of the Lord

Makes him mourn all the more

Torturing Job the handle

We have on the negative

Refusing us makes us weep

Gives us ‘new families’

Not the old ones back

Gives us new names

To cross ‘eternity’ with.

Every time we touch

No one should marry

Sweet Balkan blank

That is not despair

Parsing pretends to be

You where you cross-

dress in the dark

When the lights came on

You were a shallow

Link to causes.

*

Becomes a gravity or per force

Becomes a field our feelings do

And the way you pass through it

And the camera there where

We least expect it

‘nature’ has a gaze too ‘the animal’

Has a gaze all its own

And invisible and this is what

Is called ‘spirit’ and this what

Is immanent to the communism

You propose

The camera hovers and it is like

Us seeing how you feel me.

*

Seeing how the law grows

How it buckles under

The logic it imposes

To negate it the way

You have negated it

Is not to deny its powers

Since one stays in relation to it

Now it eclipses everyone

When before it only eclipsed some

The sun was not half as right

Then but now it is right—

Not shining in our names.

*

Using as not using

Singing as not singing

Seeing as not seeing…

--an ‘interruption’,

*

These hands weep for

What they were made for

These lungs and things

You recognize as things

But then there is the unusable

Light in the trees

What se call ‘our’ what we call ‘we’

But is not shared as love

The dredger-ship too

Close to the swimmers--

Enough to imagine disaster

There is the jetty that ends

Before the sun can reach it

The spiral indefinitely

Submerged not a metaphor

For things seen.

*

Fog here

Fog there

Lifting as

Appearance

Also has

A feel to it.

*

For Amber

Your body is the

question you put

to me a green of

‘the soul’ if there

is a soul and

souls have limbs

your body is the

question the

question of further

how we are

lacking organs

those simple things

those not so simple

things that

bodies are when

they broke down

what I thought was me

was born only to

discover through

you that ‘me’ was

a question

put to this world

different then all

the world since all

History begins in

disparity bodies

become the cause.

*

Sight hearing loss.

Loss hearing loss.

for every pit, there is a pile.

For every heap of architecture,

there is a terrestrial void.”

*

For Lee

A devil’s refusal of the Lord

Makes him mourn all the more

Torturing Job the handle

We have on the negative

Refusing us makes us weep

Gives us ‘new families’

Not the old ones back

Gives us new names

To cross ‘eternity’ with.

Every time we touch

No one should marry

Sweet Balkan blank

That is not despair

Parsing pretends to be

You where you cross-

dress in the dark

When the lights came on

You were a shallow

Link to causes.

*

Becomes a gravity or per force

Becomes a field our feelings do

And the way you pass through it

And the camera there where

We least expect it

‘nature’ has a gaze too ‘the animal’

Has a gaze all its own

And invisible and this is what

Is called ‘spirit’ and this what

Is immanent to the communism

You propose

The camera hovers and it is like

Us seeing how you feel me.

*

Seeing how the law grows

How it buckles under

The logic it imposes

To negate it the way

You have negated it

Is not to deny its powers

Since one stays in relation to it

Now it eclipses everyone

When before it only eclipsed some

The sun was not half as right

Then but now it is right—

Not shining in our names.

*

Using as not using

Singing as not singing

Seeing as not seeing…

--an ‘interruption’,

*

These hands weep for

What they were made for

These lungs and things

You recognize as things

But then there is the unusable

Light in the trees

What se call ‘our’ what we call ‘we’

But is not shared as love

The dredger-ship too

Close to the swimmers--

Enough to imagine disaster

There is the jetty that ends

Before the sun can reach it

The spiral indefinitely

Submerged not a metaphor

For things seen.

*

Fog here

Fog there

Lifting as

Appearance

Also has

A feel to it.

*

For Amber

Your body is the

question you put

to me a green of

‘the soul’ if there

is a soul and

souls have limbs

your body is the

question the

question of further

how we are

lacking organs

those simple things

those not so simple

things that

bodies are when

they broke down

what I thought was me

was born only to

discover through

you that ‘me’ was

a question

put to this world

different then all

the world since all

History begins in

disparity bodies

become the cause.

*

Sight hearing loss.

Loss hearing loss.

Sunday, July 20, 2008

BARRRRGGGGE

Check-out BARGE's Buried Treasure Island website

http://www.davidbuuck.com/barge/bti/index.html

and at Yerba Buena art center in SF

http://www.ybca.org/tickets/production/view.aspx?id=7118

Saturday, July 19, 2008

Prosodic Body Website

Daria Fain and Robert Kocik now have a website for their ongoing project, The Prosodic Body:

www.prosodicbody.org

Thursday, July 17, 2008

O Coevals (II)

So that all that gets rem

embered is "hate" and "them"

*This* is what he got

Abandoned consignment

Steeped in a sense of loss

Perfectly still with

Your bow between

The things you have been

Having been witnessed

Having witnessed

Me in the exited

Air you make me think

Of other way stations

Of possibility which

Won't suffice for nothing

Other than what's left

Over toxins trash exists

Until they erect condos

And no longer represent

Our entropy in double

Voids sustained blanks

Lyric won't admit

Some use in poetry

Except to appropriate

A general intellect

Predicts your shipwreck

Forthcoming waits in lyric

Sings and doesn't

Fulfill what is linked but

Not here like an instruction

To vanish in music

Every time we listen.

embered is "hate" and "them"

*This* is what he got

Abandoned consignment

Steeped in a sense of loss

Perfectly still with

Your bow between

The things you have been

Having been witnessed

Having witnessed

Me in the exited

Air you make me think

Of other way stations

Of possibility which

Won't suffice for nothing

Other than what's left

Over toxins trash exists

Until they erect condos

And no longer represent

Our entropy in double

Voids sustained blanks

Lyric won't admit

Some use in poetry

Except to appropriate

A general intellect

Predicts your shipwreck

Forthcoming waits in lyric

Sings and doesn't

Fulfill what is linked but

Not here like an instruction

To vanish in music

Every time we listen.

Sunday, July 13, 2008

2nd (Soma)tic Exercise Workshop

Today CA Conrad will present his second ever (Soma)tic Exercises wkshop in Philadelphia. Below are the exercises he will present. Having participated in the first of four workshops that will take place in Philadelphia this month last weekend, I can attest to the originality and value of these workshops, which seek to relocate the composing subject by injecting disequilibrium into familiar habits of attention and (un)awareness during different moments of a composing process.

The term for this process of disequilibrium Conrad coins I LOVE, and find immensely productive for thinking thru a pedagogy for (poetic) composition, THE FILTER; where to "put" a filter on experience is to enable different modes of information and attractions to permeate the site of composition.

Like Jack Spicer before him, as well as the Bernstein/Mayer of their 70s Poetry Project workshops, Conrad proves the site of composition a site of "outside," where to deliberately mediate the "self" as an intention of writing may perhaps seek what a (compositional) body *does*. That is, what a poem *can do*, and so the "person" as an extension of the poem's intuitions, desires, vicissitudes, whims, swerves...

Check-out the ongoing (Soma)tic Exercises project at: http://somaticpoetryexercises.blogspot.com

1: TIME TRAVEL NOTES: At a street corner pause to see how sunlight comes down to enter the landscape just as it has for millions of years. After a little while imagine the fern or blackberries from before the buildings and sidewalks. Was there a nest of squirrels? The death of a snake? Where are you in time? As you time travel WRITE WRITE WRITE! Take notes about what you’re seeing. PLEASE take time out to just WRITE as fast as you can after you have been absorbing your time travel. JUST WRITE, and WRITE FAST no matter if you think it looks like nonsense or not, there’s so much that wants to be revealed.

2: FOOD IS YOUR BODY IS YOUR POEMS: We will go to Whole Foods Market. Once we get into the store we will split up. Take time looking at the foods, smelling the foods, tasting samples. The cells of our bodies, and our muscles, bones, brain cells, EVERY SINGLE PART OF US is created by the food we eat. Imagine your body when looking at a piece of fruit, or a box of something frozen or in a jar. SEE yourself in this. SEE who you are in this. How do you feel when you eat certain foods? Take notes. Then find one food YOU LOVE! Instead of notes, stand in front of this food and WRITE quickly and without thinking. Find a food YOU HATE and do the very same thing. Think of food that doesn’t exist, like a piece of fruit. Invent it. Is it from a tree, a bush, or other kind of plant or vine? What does this fruit taste like and look like? Where would you find it in the store? Go to where it would be if it existed and SEE IT THERE. Does this fruit have special powers when you eat it, like the power of invisibility? Take notes.

3: STATE OF THE STATUES : There are no less than 16 statues in the Logan Circle Fountain area, such as Rodin’s THINKER, Shakespeare, famous revolutionaries, dinosaurs, Jesus, etc. Imagine these statues have been wanting to converse with one another for decades but are too spread out to do so. Choose two, or three on the map provided and go to them, spending time thinking what they would have to say and share with the others you choose. Take notes on the statues, take some time after you have absorbed the statue and write whatever you want and as fast as you can. Suppose that one of the statues tells you that there is a MISSING statue, a statue which has been removed many years ago before you were born. What was it? Take notes and write as much as you can.

THE FILTERS

In (Soma)tic Poetry THE FILTERS function as the focal point of the information gained through the exercises to shape the poem. For this second day of 3 maneuvers FILTER with the two words: FORSEE (or FORSEEABLE or any other form of this word), and NAKED. With THE FILTERS you take all of your notes and begin to write poetry about or through these two words, shaping and editing as you go. But it’s important to note that THE FILTERS are only guides, and to help you shape the poem.

YOUR TAKE-HOME EXERCISE

What poem by someone else is your favorite poem? Copy it out by hand (please do not type it) on unlined paper. I ask that you use unlined paper so as not to limit the FEELINGS you may have when copying it out. Once you have finished copying the poem go to the blank spaces in the margins or bottom, or wherever on THAT page and write VERY QUICKLY AND WITHOUT THINKING notes about HOW YOU FEEL AT THAT MOMENT. Later that same day eat some dark chocolate and immediately begin copying the same poem again on another piece of unlined, clean paper. Take MORE notes, and WRITE AS FAST AS YOU CAN ABOUT HOW YOU ARE FEELING AT THAT MOMENT. The next morning get in the shower, scrubbing well, then end the shower with COLD WATER, then get out, quickly dry off, and immediately begin the process again of copying the poem by hand and making note of HOW YOU ARE FEELING. After this take all the notes you have made and pull words out of those notes to form a poem FILTERED through the words MAUL and MEASURE.

Saturday, July 12, 2008

Being Arthur Russell

My percept a feeling divides

Like cells divide the eye

And sunset this and clouds that

Point to which drums shoot

The air up shake their fists

In the air some meaning of

Us was in your airs drip

ping down from the present

A series of strings verbs

Spiraling down from which

Identification is not your

Eyes seeing the wind skim

Across what iteration and

Irritants nearly touch

An idea of skin our image-

Forming suffused by music

Imagine a night-light’s

Inner life imagine forgetting

The meaning of all those

Little words like a conse

quence this breath burdened

By a bow and what the voice

Can do articulation folded

The air around in the event

Of this note duree betrayed

My heart of Avenue A in

The rain pigeons seemed to

Circle the sun so this was us

Their wings creased like

Gold leaf on a knife that is

The matting of our days

A way their simultaneity was

Not entirely in synch with

Anything one of them did

Or made social by a sing

ular turn of their wings.

Like cells divide the eye

And sunset this and clouds that

Point to which drums shoot

The air up shake their fists

In the air some meaning of

Us was in your airs drip

ping down from the present

A series of strings verbs

Spiraling down from which

Identification is not your

Eyes seeing the wind skim

Across what iteration and

Irritants nearly touch

An idea of skin our image-

Forming suffused by music

Imagine a night-light’s

Inner life imagine forgetting

The meaning of all those

Little words like a conse

quence this breath burdened

By a bow and what the voice

Can do articulation folded

The air around in the event

Of this note duree betrayed

My heart of Avenue A in

The rain pigeons seemed to

Circle the sun so this was us

Their wings creased like

Gold leaf on a knife that is

The matting of our days

A way their simultaneity was

Not entirely in synch with

Anything one of them did

Or made social by a sing

ular turn of their wings.

Tuesday, July 08, 2008

A (Soma)tic Exercise

So rows vanish

Points me wood

Does this circle

End what the

Fuck is going

On these are

Just some notes

Among the muggy

Cars and flag

Torn filters throw

The wreck off

Wherever we go

Statues mark this

Place tho nothing

Happens seasons reverse

On opposite days

I'm not sorry

For being a

Discourse connect the

Lines in gasoline

It is summer

In the snow

A public space

Seems to float

Through me there's

A street above

Those open leaves.

Points me wood

Does this circle

End what the

Fuck is going

On these are

Just some notes

Among the muggy

Cars and flag

Torn filters throw

The wreck off

Wherever we go

Statues mark this

Place tho nothing

Happens seasons reverse

On opposite days

I'm not sorry

For being a

Discourse connect the

Lines in gasoline

It is summer

In the snow

A public space

Seems to float

Through me there's

A street above

Those open leaves.

Monday, July 07, 2008

At Long Beach Notebook

I will be reading next week in Long Beach, CA with Rob Halpern and Amanda Ackerman for Jane Sprague's seminal events series, Long Beach Notebook. Here is the ad for the event:

Dear Friends,

Please join us next Saturday, July 12 2008 in Long Beach, California to hear the work of Amanda Ackerman, Thom Donovan and Rob Halpern.

Long Beach Notebook begins at 8:00 pm. The event takes place at the home office of Palm Press: 143 Ravenna Drive, Long Beach, CA 90803 (use Mapquest or Google Maps for directions).

***

Amanda Ackerman lives in Los Angeles where she writes and teaches. She is co-editor of the press eohippus labs. She is a member of UNFO (The Unauthorized Narrative Freedom Organization) and writes as part of Sam or Samantha Yams. She is also a member of the event space Betalevel. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in flim forum; String of Small Machines; The Physical Poets; WOMB; and the Encyclopedia Project, Volume F-K. With Harold Abramowitz, she is also co-author of the book Sin is to Celebration, soon to be published by House Press in the fall.

Thom Donovan lives and works in Manhattan, where he edits Wild Horses of Fire blog (whof.blogspot.com), curates the events series Peace On A, and coedits ON, a new magazine for contemporary practice. He attended the Poetics Program at SUNY-Buffalo and is an ongoing participant in the Nonsite Collective.

Rob Halpern is the author of Rumored Place, Imaginary Politics, and Snow Sensitive Skin (co-authored with Taylor Brady). Disaster Suites will be published this Summer by Palm Press. He's currently co-editing the writings of the late Frances Jaffer together with Kathleen Fraser, and translating the early essays of Georges Perec, the first of which, "For a Realist Literature," can be found in the recent issue of Chicago Review. He lives in San Francisco.

***

From Disaster Suites by Rob Halpern:

This war

Of want

Says what

I want

To say

To you

Of dreams

Or need

We need

Not speak

To speak

Of wars

Of want

I come

To love

So late

To you

My lost

- marine.

***

from O Coevals by Thom Donovan

We witness bells that this was theirs

That shade equals sun in exquisiteness

Non-identities piling up like pylons

A physics without cars beings without

Impact move to what here to what

Their equated it I feel so much pressure

Around you to burn a discourse and not

Touch any time we were or event

Living us so live my life will never finish

What my death leaves unfinished this

Town never seems to work those sovereign

Stumps sing us into battle effects

Of power fires hymns even the sun

Forgot to burn so sing patiency which

Organs won't be consumed what ex

change won't always be sung for being

Too far from off-shore what bodies we

Haven't won't account for limbs little

Substances Nature complicit with who

Gets to live grieves its contrivance.

***

from Amanda Ackerman:

Here on fire we remove the husk of the seed with the aching to peel back with the aching to hear; to touch is to look, the seed looks like and says this:

It is spring, but my corn does not want to sell her rooster. If I wait another year, the rooster will be considered old, quite old, very old. And having been an upright and tireless citizen his whole life, always dressed in devoted red, always smelling like humid, dank gems and unbottled musk, the rooster will start to make up stories about how he fought in the war, welded the sides of tanker ships, wore a shattered, sandy green army helmet. Then no one will want to buy him, it's just a matter of timing. Let him stay and my lips will keep moving, turn the shapes of fortified roots, and I can stay forever awake in the dark folds of nucleotides, always siding with what is right, always siding.

***

See you then...

www.palmpress.org

Friday, July 04, 2008

People Are Strange (When You're a Stranger)

Presented by Marisa Olson

Tuesday, July 8, 2008 at 8pm

55 33rd Street, 3rd Floor

Brooklyn, NY

Ticket Price - $6

"People Are Strange" will be a night of multimedia performance and projections revolving around the release of Marisa Olson's new artist book, Poems I Wrote While Listening to the Doors, 1992-1994 (Before I found the internet). Written by the artist in high school "while burning incense and listening to the Doors," whose lead singer she then perceived as an "under-appreciated poetic genius," they are now a record of an active artist's earliest creative efforts and they provide evidence of an obsession with music, genre, psychology, and personal narrative that shines through in her more recent artworks. The title and form of the writings refers to a previous obliviousness to the internet, despite the fact that network culture (and particularly blogging or online diarism) have ultimately had a huge impact upon her practice. This evening will continue Olson's ongoing interest in public humiliation and the aesthetics of failure, from which she believes we can learn more, politically and personally, than from success. A handful of distinguished poets will read short excerpts from the book, a few experimental musicians will turn her words into lyrics, and of course Olson will do some singing and reading of her own. All of this will be mediated by live visual projections and recorded music videos created by the artist in an effort to reconcile past and present, word and image. Participating poets and musicians include Thom Donovan, Stephanie Gray, Christian Hawkey, Dorothea Laskey, and members of the bands Professor Murder, Aa, and Taigaa.

About Marisa Olson

Marisa Olson's work combines performance, video, sound, drawing, and installation to address intersections of pop culture and the cultural history of technology, as they effect the voice, power, and persona. Her work has recently been presented by the Whitney Museum of American Art, Centre Pompidou-Paris, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the 52nd International Biennale di Venezia, the Edith Russ-Haus fur Medienkunst, Nederlands Instituut voor Mediakunst/Montevideo, the British Film Institute, the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, Glowlab, and Free103Point9. She is also a founding member of the Nasty Nets "internet surfing club" whose new DVD recently premiered at the New York Underground Film Festival. Her work has been written about in Artforum, Art in America, Folha de Sao Paolo, Liberation, the Village Voice, New York Magazine, and elsewhere. While Wired has called her both funny and humorous, the New York Times has called her "anything but stupid." Marisa studied Fine Art at Goldsmiths College-London, History of Consciousness at UC Santa Cruz, and Rhetoric at UC Berkeley.

About Light Industry

Light Industry is a new venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York. Developed and overseen by Thomas Beard and Ed Halter, the project has begun as a series of weekly events at Industry City in Sunset Park, each organized by a different artist, critic, or curator. Conceptually, Light Industry draws equal inspiration from the long history of alternative art spaces in New York as well its storied tradition of cinematheques and other intrepid film exhibitors. Through a regular program of screenings, performances, and lectures, its goal is to explore new models for the presentation of time-based media and foster a complex dialogue amongst a wide range of artists and audiences within the city.

Tuesday, July 01, 2008

Black Field II

What I forgets to leave

Here and what I forgets

It is here not home to itself

Like bodies the fan whirs

In the room a metaphor

Or something for conscious

ness this voice around

The air is something you

Swear to this that you will

Be you to me so this darkness

Where I must imagine your

Touch is more than me

Or you this discourse of

The senses more than any

thing one amounts to.

Here and what I forgets

It is here not home to itself

Like bodies the fan whirs

In the room a metaphor

Or something for conscious

ness this voice around

The air is something you

Swear to this that you will

Be you to me so this darkness

Where I must imagine your

Touch is more than me

Or you this discourse of

The senses more than any

thing one amounts to.

Friday, June 27, 2008

Julie Patton's Hear In (Ad)

Julie Patton's "Hear in: A walk and talk about the East Village (above/beyond the usual rhythms, lines of sight)" will kick off at St. Mark's Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall/West Yard, Monday, June 30 at 1:00 pm. The event is free and open to the public. Children and animals welcome.

Julie patton is a 2007 Artists' Fellowship recipient of the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA). This presentation is co-sponosred by Artists & Audiences Exchange, a public program of NYFA.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Discourse as Muse (Note)

Last night I presented to Andrew Levy's class at NYU, "Writing that Matters," along with Julie Patton and Brenda Iijima. Among the materials I read aloud included a forthcoming editorial for ON, a publication I am coediting with Kyle Schlesinger & Michael Cross for emergent critical discourse about poetics, and a statement regarding "discourse as muse" which I include here.

A lengthier consideration of the notion of discourse as muse would make case studies from poets and artists who have made of their work allegories of social exchange and movement such as Robert Creeley, Jack Spicer and Hannah Weiner (tho, arguably, every writer or artist's work, if only in negative, presents such an allegory)...

***

Discourse As Muse

I have been thinking about the old idea of poetry and “the muse”. If the muse is no longer a figure of divine inspiration, nor one figured by Romantic love—the love of a man for an indealized woman, in particular—than what could it be? What is a contemporary muse, if not such things? In this presentation, I would like to think about the figure of muse through a different set of terms and assumptions concerning where poetry comes from, and how it operates and subsists in the world. I will do this by claiming “discourse” as the contemporary poet’s muse, and my muse in particular.

Discourse, literally, refers to a site of articulation or locution that is more or less continuous and shared. It is perhaps what is held in common without being completely shareable. In this way it does not represent a fantasy of pure communion, or transubstantiation (father, son, holy spirit stuff, etc.)

To discourse, in common speak, is to exchange words, or hold conversation. In the work of late 20th century French literary philosophers like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault the term discourse usually accompanies what Barthes has referred to as “the death of the author” and Foucault the "author function". Where an old idea of the author has the author as a figure of isolated genius and radical individuality, Foucault, Barthes and a host of other writers in the 20th century show any author to in fact comprise a network of other individuals, technologies, institutions, and economic exchanges. Likewise, an author does not make but one text, but a text that is many in being singular, and in being attributed to one author in name.

Whereas detractors of this notion of discourse have lamented the loss of the author as the central character in the drama of literary exchange (making and reception), and others celebrated it, I and many of my contemporaries see it as a place for productive exchange, and for making work that matters for community building and towards the nourishment of a larger social sphere. To claim discourse as muse, I believe, is to cast the old figure of the muse with a renewed character. Whereas before an ethereal spirit and equally ethereal object of desire embodied muse, where discourse become muse the poem reveals itself as a site of social exchange within a network of other sites.

A lengthier consideration of the notion of discourse as muse would make case studies from poets and artists who have made of their work allegories of social exchange and movement such as Robert Creeley, Jack Spicer and Hannah Weiner (tho, arguably, every writer or artist's work, if only in negative, presents such an allegory)...

***

Discourse As Muse

I have been thinking about the old idea of poetry and “the muse”. If the muse is no longer a figure of divine inspiration, nor one figured by Romantic love—the love of a man for an indealized woman, in particular—than what could it be? What is a contemporary muse, if not such things? In this presentation, I would like to think about the figure of muse through a different set of terms and assumptions concerning where poetry comes from, and how it operates and subsists in the world. I will do this by claiming “discourse” as the contemporary poet’s muse, and my muse in particular.

Discourse, literally, refers to a site of articulation or locution that is more or less continuous and shared. It is perhaps what is held in common without being completely shareable. In this way it does not represent a fantasy of pure communion, or transubstantiation (father, son, holy spirit stuff, etc.)

To discourse, in common speak, is to exchange words, or hold conversation. In the work of late 20th century French literary philosophers like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault the term discourse usually accompanies what Barthes has referred to as “the death of the author” and Foucault the "author function". Where an old idea of the author has the author as a figure of isolated genius and radical individuality, Foucault, Barthes and a host of other writers in the 20th century show any author to in fact comprise a network of other individuals, technologies, institutions, and economic exchanges. Likewise, an author does not make but one text, but a text that is many in being singular, and in being attributed to one author in name.

Whereas detractors of this notion of discourse have lamented the loss of the author as the central character in the drama of literary exchange (making and reception), and others celebrated it, I and many of my contemporaries see it as a place for productive exchange, and for making work that matters for community building and towards the nourishment of a larger social sphere. To claim discourse as muse, I believe, is to cast the old figure of the muse with a renewed character. Whereas before an ethereal spirit and equally ethereal object of desire embodied muse, where discourse become muse the poem reveals itself as a site of social exchange within a network of other sites.

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

PhillySound at FANZINE

check out PhillySound poets at FANZINE

with an editorial by CAConrad

http://thefanzine.com/articles/poetry/254/phillysound_poets

Monday, June 23, 2008

The Children

check out this amazing project by Aram Saroyan and Philip Whalen at Big Bridge:

http://www.bigbridge.org/AS-CH.HTM

"That summer my father took my sister Lucy and me to Europe and Dick gave me a box of film as a going away gift. My father encouraged me to photograph street kids, and I came home from the trip with many rolls of exposures. The art director Marvin Israel accepted eight photographs for a spread in Seventeen, for which we each won an Art Directors award. Years later, now a writer, I published a book that included many of those photographs, Words & Photographs (Big Table, 1970). During the late sixties, I also did a mock-up of a second book of (mostly) different photographs from the same visit to Europe and sent it to Philip Whalen in Kyoto to write something on the page opposite each photograph. As I sensed he might, Phil turned the request around quickly. I received the marvelous text here virtually by return mail.

When I approached the European and American children in these photographs, I was still a child myself, and I think the transparent parity in some of the images is due to my being more an accessory of the camera than the other way around. Un-intimidated by the photographer, kids seemed to engage the medium with a straightforward sense of its potential, and I was on hand to make the picture.

Then, as I see it, a miracle accrued. Well-nigh half a century went by, and I discovered again these images and fell in love with some of these subjects whom I knew only for an anonymous moment and who have long since ceased to be children. It's not unlikely that some of them have ceased to be, period."

~ from *The Children*, intro and photos by Aram Saroyan, poems by Philip Whalen

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Kristin Prevallet responds to Power and Performance

Kristin Prevallet generously provided the following reflection after I solicited her and others to respond in writing to performances by David Buuck, Julie Patton and Chen Tamir at Peace On A the Sunday before last...

***

Many layers of reflection happening after The Event.

1st thought: Performance Art - even in its non-site ambitions - does not level race and class. None of the examples presented level race and class. Race and class may be confronted, boundaries may temporarily be re-drawn, questions and reflections may happen in the condensed space of the performance, and maybe the edge of race and class is revealed. But it's still sharp. It's not leveled.

How I came into the space: I was already thick-thinking about Laura Elrick's brilliant essay about poetry and ecology. I have also been reading "Ecology against Capitalism" by John Bellamy Foster. I came to the space with recurring thoughts about the ways that the morality of production needs to be challenged / changed in this production-based country. (Foster gets into this.) Why is it ok for me as an artist and writer to produce, produce, produce, but it is not ok for logging companies to cut drown trees in order that products can be invented that allow me to produce produce produce? It's what Foster calls "The Treadmill of Production." I'm practicing non-production at the moment, trying to figure all this out in terms of my own psyche and reliance on production as the key to happiness.

However, because I can't help producing (ideas, images, words) I have been working with performance which as David and Julie manifested and Chen demonstrated, allows for what Laura Elrick states as her priority as a poet at this moment: "Recognizing our collective participation in this extension might bring about new ways of engaging in the practice of poetry, a poetics, in short, that points less toward a fetishistic valorization of “the text” as object (form & content) and more toward an investigation of mediated textualities that intervene in (and experiment through) the mode of production, circulation and exchange." I'm located here in this moment of thinking.

Here's where I'm at, for the archives:

http://www.asu.edu/pipercwcenter/how2journal/vol_3_no_2/performance/prevallet-cruelpoemperf.html

Julie, spontaneous, talks poems. She tries to initiate immediate audience responses. It doesn't quite work - but it does bring me (maybe us?) to the edge - the edge of a confort zone. Should I start singing? I couldn't at that moment. But I did leave a softer person in the sense that after I left the event, I practiced loosening the boundaries between myself and passers-by (by smiling, saying "hi!" to whoever caught my eye.) Just a little gesture, but a homage to the energy-transference that occurred.

David shows slides, but is conscious (and says so) about the conflict between showing slides to document an event and the immediacy of the event itself. Were the slides necessary? Could he have just rubbed the poison dirt in his face and spoke spontaneously for 20 minutes, ending in his amazing chant to resurrect the dead, become the earth? Would that have been even more powerful? Was the hyper-self consciousness of the slide-show necessary?

I am moved in the direction of performance by deep conversations with my engaged contemporaries - Peace on A, Laura Elrick, the WACK! show at PS1 (and the catalogue), Julie, David, Rodrigo. All working to transmute the form of the poem into live space / action. Change the nature of poem-production and poem-reception. (Sure - it's all been done before. But it's being done again, NOW. Locating non-site in this very particular and charged moment - trying it out at Peace-on-A.)

***

Many layers of reflection happening after The Event.

1st thought: Performance Art - even in its non-site ambitions - does not level race and class. None of the examples presented level race and class. Race and class may be confronted, boundaries may temporarily be re-drawn, questions and reflections may happen in the condensed space of the performance, and maybe the edge of race and class is revealed. But it's still sharp. It's not leveled.

How I came into the space: I was already thick-thinking about Laura Elrick's brilliant essay about poetry and ecology. I have also been reading "Ecology against Capitalism" by John Bellamy Foster. I came to the space with recurring thoughts about the ways that the morality of production needs to be challenged / changed in this production-based country. (Foster gets into this.) Why is it ok for me as an artist and writer to produce, produce, produce, but it is not ok for logging companies to cut drown trees in order that products can be invented that allow me to produce produce produce? It's what Foster calls "The Treadmill of Production." I'm practicing non-production at the moment, trying to figure all this out in terms of my own psyche and reliance on production as the key to happiness.

However, because I can't help producing (ideas, images, words) I have been working with performance which as David and Julie manifested and Chen demonstrated, allows for what Laura Elrick states as her priority as a poet at this moment: "Recognizing our collective participation in this extension might bring about new ways of engaging in the practice of poetry, a poetics, in short, that points less toward a fetishistic valorization of “the text” as object (form & content) and more toward an investigation of mediated textualities that intervene in (and experiment through) the mode of production, circulation and exchange." I'm located here in this moment of thinking.

Here's where I'm at, for the archives:

http://www.asu.edu/pipercwcenter/how2journal/vol_3_no_2/performance/prevallet-cruelpoemperf.html

Julie, spontaneous, talks poems. She tries to initiate immediate audience responses. It doesn't quite work - but it does bring me (maybe us?) to the edge - the edge of a confort zone. Should I start singing? I couldn't at that moment. But I did leave a softer person in the sense that after I left the event, I practiced loosening the boundaries between myself and passers-by (by smiling, saying "hi!" to whoever caught my eye.) Just a little gesture, but a homage to the energy-transference that occurred.

David shows slides, but is conscious (and says so) about the conflict between showing slides to document an event and the immediacy of the event itself. Were the slides necessary? Could he have just rubbed the poison dirt in his face and spoke spontaneously for 20 minutes, ending in his amazing chant to resurrect the dead, become the earth? Would that have been even more powerful? Was the hyper-self consciousness of the slide-show necessary?

I am moved in the direction of performance by deep conversations with my engaged contemporaries - Peace on A, Laura Elrick, the WACK! show at PS1 (and the catalogue), Julie, David, Rodrigo. All working to transmute the form of the poem into live space / action. Change the nature of poem-production and poem-reception. (Sure - it's all been done before. But it's being done again, NOW. Locating non-site in this very particular and charged moment - trying it out at Peace-on-A.)

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Black Field I

~ for Dottie and Conrad

I have been thinking about you

As a kind of goo

For the mind to have visions

That are only of the mind

Or like that sliver

We enter when we write

And it is as though

Ideas had to come from some place

And there are words for those places

Or rather those places are

A kind of fundamental syntax

For the world and we need only

Pluck them from the air

We need only pluck them

From under your shallowest

Surface to say anything we want

Is it true you are the future in fact

The thinnest future we have

When we attend each other

The mind of each other as a delay

How patiently we must

Await each one each other's

I have been thinking about you

As a kind of goo

For the mind to have visions

That are only of the mind

Or like that sliver

We enter when we write

And it is as though

Ideas had to come from some place

And there are words for those places

Or rather those places are

A kind of fundamental syntax

For the world and we need only

Pluck them from the air

We need only pluck them

From under your shallowest

Surface to say anything we want

Is it true you are the future in fact

The thinnest future we have

When we attend each other

The mind of each other as a delay

How patiently we must

Await each one each other's

Thursday, June 12, 2008

Power comes...

to those who (don’t)

wait--language an in

equality what you l

end and what I actu

ally take--privilege

and what I discard I

abandon in principle

and yet know--that I

do this complicity p

okes out the old su

n’s eyes--makes some

verbs from what nou

ns controlled--pinpo

inting the voice li

ke an arrow rhetoric

silver-tongued pois

on-tipped angel--bin

ging on dominion so

ul saver and sovere

ign--must I speak to

an object appreciat

es shit--zealous cont

agion, zealous anti

thesis the undead,

unmourned, unliberat

ed, disavowed as a

kind of third sex--

seducing us back from

that bad fantasy of

ways we have chosen.

wait--language an in

equality what you l

end and what I actu

ally take--privilege

and what I discard I

abandon in principle

and yet know--that I

do this complicity p

okes out the old su

n’s eyes--makes some

verbs from what nou

ns controlled--pinpo

inting the voice li

ke an arrow rhetoric

silver-tongued pois

on-tipped angel--bin

ging on dominion so

ul saver and sovere

ign--must I speak to

an object appreciat

es shit--zealous cont

agion, zealous anti

thesis the undead,

unmourned, unliberat

ed, disavowed as a

kind of third sex--

seducing us back from

that bad fantasy of

ways we have chosen.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)