4. Do Angels See Anamorphically?

In Wim Wenders *Wings of Desire* angels do not see in black and white or color, but in sepia. Likewise, while Wender’s angels are telepathic (capable of reading the thoughts of others), and can teleport (be at any place instantly), they cannot experience the five senses of mortal beings, nor can they know death (Bruno Ganz is perplexed when he discovers his head to be bleeding) or sexual relations (Ganz, of course, eventually trades-in his wings to be with a human lover).

In Adrian Lyne’s *Jacob’s Ladder* we do not see from the point of view of Danny Aiello’s Louis, however (as a Sufi Angel) we may imagine him to see like the Persian Sufi Sa’id when the poet writes:

In Adrian Lyne’s *Jacob’s Ladder* we do not see from the point of view of Danny Aiello’s Louis, however (as a Sufi Angel) we may imagine him to see like the Persian Sufi Sa’id when the poet writes: If the sword of your anger puts me to death,

My soul will find comfort in it.

If you impose the cup of poison upon me,

My spirit will drink the cup.

When on the day of resurrection

I rise from the dust of my tomb,

The perfume of your love

Will still impregnate the garment of my soul.

For even though you refused me your love,

You have given me a vision of You

Which has been the confidant of my hidden secret.[6]

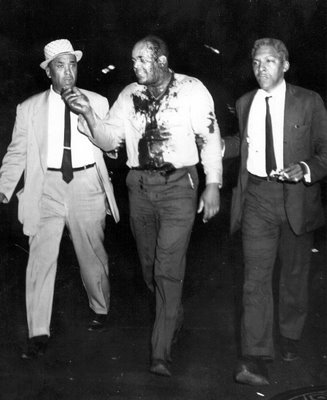

Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins) encounters any number of angels and demons as his soul transmigrates after a bloodbath among his troop in Vietnam, the terror of his Bardo given cinematic fact not only by the appearance of the demons who confront him--those without faces, eyes, and often limbs--and the predictions of a fortuneteller who tells him his palm is without a “life line,” and that he is therefore already dead; but also by the film’s swish pans which indicate “the fear of death-as-undeath that frightens one to death”[7].

In Chris Marker’s documentary for Andrei Tarkovsky, *A Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich*, the French filmmaker points out how Tarkovsky’s characteristic camera angle differs from that of the typical American Western: where the camera of the Western points at an angle to the sky, Tarkovsky’s tends to angle towards the earth. This difference in camera angle indicates an important difference between American and Russian spirituality, as the American is regenerated by the transcendental promise of “big sky,” and the Russian by laying down in the earth, as many of Tarkovksy’s characters often do throughout his films.

In Chris Marker’s documentary for Andrei Tarkovsky, *A Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich*, the French filmmaker points out how Tarkovsky’s characteristic camera angle differs from that of the typical American Western: where the camera of the Western points at an angle to the sky, Tarkovsky’s tends to angle towards the earth. This difference in camera angle indicates an important difference between American and Russian spirituality, as the American is regenerated by the transcendental promise of “big sky,” and the Russian by laying down in the earth, as many of Tarkovksy’s characters often do throughout his films.One may often have the sense in Tarkovsky’s films that the point-of-view is that of an angel, or God itself. The concluding scene from *Andrei Rublev* provides one example of this, an aerial shot of the bell hoisted by an elaborate series of ropes; in the concluding scene of *Solaris*, the camera tracks revealing Kris’s home on earth to actually be located on an island of the oceanic planet.

In the opening shots of Alexander Sokurov’s *Whispering Pages* the camera, affixed to a boat which bobs in the water of a canal, tracks a building across the water while the shot is obscured by plumes of vapor. Birds that would seem doubly exposed fly in front of the screen and then land on the water; so ghostly are the birds that it comes as a surprise when they disturb the water. In a later scene, men and women jump from a landing to a place below, off-screen. While they jump the viewer hears a soundtrack, affected by reverb, of men and women talking loudly, cackling and laughing. These reverberating voices are non-diegetic, not matching realistically with the scene of the men and women jumping. In *Mother and Son*, the camera slowly descends as it cranes the couple sitting on a bench, looking at a photo album together. As the camera also twists while it descends, its motion mirrors the twisting trunks and branches of a tree beneath which the couple sit. In *Russian Ark*, Sokurov’s use of steady cam provides a constant sense that the camera is disembodied as it tours the St. Petersburg Hermitage. During the film, the camera often makes a focal adjustment that produces a feeling of vertigo in the viewer. The vertiginous effect of this adjustment—as if the lens were zooming-out while the camera tracked forward—is heightened by a *glissando* in the soundtrack. In Alfred Hitchcock’s *Vertigo* the viewer encounters a similar effect as Johnny-O (Jimmy Stewart) struggles to ascend the staircase at the Mission. Is this vertiginous effect of the camera in fact an effect of time travel? Both films travel “back in time”: *Vertigo* by reincarnation, *Russia Ark* by reenacting historical scenes from the Hermitage, and the nostalgic reminiscences of the film’s guide.

While angels may see by steady cam and by slow tracking shots accompanied by a non-diegetic soundtrack, I wonder if they do not also see anamorphically? Along with the American filmmakers Sidney Petersen and Stan Brakhage (to whom Petersen gave his anamorphic camera lens as a gift), Alexander Sokurov is one of the great filmmakers to extensively employ anamorphic lenses—an optical technology originally imported from the Middle-East to Europe in the 16th Century[8]. In anamorphic illustration one finds an “accelerated” or “decelerated” (Baltrusaitis) state of optical abstraction, whereby one must look “awry,”[9] at an extreme angle to the plane of the picture, in order to see images in their correct proportions. In film, anamorphosis tends to elongate figures and give a swirling effect to their motions. By Sokurov’s use of anamorphic camera lenses, the filmmaker draws the viewer’s attention to a world deformed, and thanatological in this deformation. The anamorphic effects of *Mother and Son* are particularly telling of the optical phenomenon’s relation to death, as it gives due form to the mother’s *rigor mortis* at the conclusion of the film, and throughout the film all of nature--the trees, for instance, upon which the son leans and cries--seem themselves to mourn the mother’s death by the fact of their blurry elongations and wet, saturated colors. Likewise, anamorphoses provides a disorienting sense of space in *Mother and Son* and the film’s sequel, *Father and Son*, as the son of the former film (played by Aleksei Ananishnov) walks along a dirt path disappearing behind what appears a far away brush only to emerge directly in front of the camera, posing in *ruckenfigur*. Sokurov’s viewer may feel a similar sense of spatial disorientation as the two boys of *Father and Son* ride a trolley together, and eventually stand on an escarpment overlooking the city.

While angels may see by steady cam and by slow tracking shots accompanied by a non-diegetic soundtrack, I wonder if they do not also see anamorphically? Along with the American filmmakers Sidney Petersen and Stan Brakhage (to whom Petersen gave his anamorphic camera lens as a gift), Alexander Sokurov is one of the great filmmakers to extensively employ anamorphic lenses—an optical technology originally imported from the Middle-East to Europe in the 16th Century[8]. In anamorphic illustration one finds an “accelerated” or “decelerated” (Baltrusaitis) state of optical abstraction, whereby one must look “awry,”[9] at an extreme angle to the plane of the picture, in order to see images in their correct proportions. In film, anamorphosis tends to elongate figures and give a swirling effect to their motions. By Sokurov’s use of anamorphic camera lenses, the filmmaker draws the viewer’s attention to a world deformed, and thanatological in this deformation. The anamorphic effects of *Mother and Son* are particularly telling of the optical phenomenon’s relation to death, as it gives due form to the mother’s *rigor mortis* at the conclusion of the film, and throughout the film all of nature--the trees, for instance, upon which the son leans and cries--seem themselves to mourn the mother’s death by the fact of their blurry elongations and wet, saturated colors. Likewise, anamorphoses provides a disorienting sense of space in *Mother and Son* and the film’s sequel, *Father and Son*, as the son of the former film (played by Aleksei Ananishnov) walks along a dirt path disappearing behind what appears a far away brush only to emerge directly in front of the camera, posing in *ruckenfigur*. Sokurov’s viewer may feel a similar sense of spatial disorientation as the two boys of *Father and Son* ride a trolley together, and eventually stand on an escarpment overlooking the city.In the Quay Brothers only live-action film, *Institute Benjamenta* (1995), Jakob enrolls in the institute of the film’s title to be trained as a butler. In being trained, he first sees his lessons as repetitive and pointless, however gradually discovers in them an occult order. The exercises of these lessons, given by the master of the school, Frau Benjamenta--making a perfect circle of a cascaded set of spoons, folding napkins, reciting phrases one might say to the master of a house, swaying and intoning in unison with the other students--indicate a Grace not unlike that Heinrich von Kleist observes in marionette theater: “But, as the intersections of two lines, from the one side of a point, after passing through the infinite, returns suddenly to the other side; or, the image of a concave mirror after moving into the infinite appears suddenly again, near or before us; so, when Knowledge has gone, so to speak, through the infinite, Grace returns again, appearing at the same time, most purely, in the structure of a body which has either no knowledge, or an infinite knowledge, to wit: in a marionette or in a God.” In the total obedience of the Quay Brothers’ butler, the butler becomes like a marionette, and thus also like a God, involved with a universe of infinite mechanistic forces. It should come as no surprise that *Institute Benjamenta* was produced by a pair of filmmaker’s best known for their exquisite animation, insofar as contemporary film animation takes up, cinematically, problems similar to those of marionette theater and dance. Like the Nietzschean dancer in whom Alain Badiou recognizes the innocence of “a body before the body”[9], the butlers and animation figures of the Quay Brothers’ films overcome impulses to be mastered *by* (and therefore gain mastery *of*) invisible forces, perhaps giving answer to Simone Weil’s enigmatic question: “What wings raised to the second power can make things come down without weight?”.

Is the anamorphic distortion of a wall-painting in *Institute Benjamenta* a kind of key to the film’s own search for Grace, where such images are not only typically corrected by “looking awry,” but as well through the use of concave mirrors? As Jakob walks the labyrinthine corridors of the institute by night, he encounters a series of curiosities, including a clock whose second hand inexplicably disturbs a pile of dust as it traces its path, as well as jars containing the dried reliquary objects of deer. When Jakob leaves the hallway where the viewer sees an anamorphic wall-painting, he closes a door behind him and looks through a hole in the door to see, at the correct angle of the painting, a depiction of two deer engaged in coitus. Is the order of angels, like that of the institute’s labyrinthine architecture or the graceful pedagogy of Frau Benjamenta’s lesson plans, an anamorphic one insofar as it requires an optical correction to discover it? In such corrections may reside the necessary beauty of angelic intuitions.